Depot [Storage] (2009)

›An artist works in the depot of the Stadtmuseum Tübingen. For weeks he explores the areas and corridors, draws selected shelves and discovers a fascinating order of the things, to which so far nobody gave attention: There is less the hoarded objects in the shelf, which captivated him, than rather their protrusions, the remains of the things thus, which could not be made quite adapted for the even beat of the shelf rows.

The drawings, made in the depot, represent the objects outside the order and form the basis for the further work in the studio. They are three-dimensional converted on large paper sheets, in each case representing a selected shelf unit. Thus becomes visible, what one did not notice in the depot: Now the object parts – one recognizes a door handle, besides, there a piece of wicker basket, here the sloping edge of an archive box –, are protruding from the even surface of the paper. They show not the disorder of the material archive, but document in ironical way similarly the mediating attempts of humans to the fractiousness of things.‹

Evamarie Blattner, Curator Stadtmuseum Tübingen

An Archive of the Archives

Herbert Stattler’s artistic research in the depot of the Stadtmuseum Tübingen

Most of the time a museum conceals more than it reveals: In its archives with its shelves, cabinets and drawers the greater part of the inventory remains unknown to the visitor, to whom only a small range of objects is presented in the exhibition rooms. In the archives the »aesthetics of the concealed« is valid – many things remain invisible for a long time, sometimes not even the scientific staff has ever seen… read more

Drawings

Paper Objects

Untitled (Lotte Reiniger), 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm

Detail Untitled (Lotte Reiniger), 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm

Untitled (Boltz, Eckardt, Mueller & Graef, …), 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x73 cm

Detail Untitled (Boltz, Eckardt, Mueller & Graef, …), 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x73 cm

Untitled (Bassenge, Dostmann, Mayer, …), 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm

Detail Untitled (Bassenge, Dostmann, Mayer, …), 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm

Untitled (Depperich, Schwabinger, Vogt, …), 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm

Detail Untitled (Depperich, Schwabinger, Vogt, …), 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm

Untitled (Rosa Klett, Kueferwerkzeug, Zimmer hinten rechts), 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm

Detail Untitled (Rosa Klett, Kueferwerkzeug, Zimmer hinten rechts), 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm

Untitled (Buehler, Honold, Zimmer, …), 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm

Detail Untitled (Buehler, Honold, Zimmer, …), 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm

Untitled (2 Archivschachteln), 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm

Detail Untitled (2 Archivschachteln), 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm

Untitled (Lotte Reiniger), 2009, paper / beeswax, 102 x 73 x 6 cm

Detail Untitled (Lotte Reiniger), 2009, paper / beeswax, 102 x 73 x 6 cm

Untitled (Boltz, Eckardt, Mueller & Graef, …), 2009, paper / beeswax, 102 x 73 x 6 cm

Detail Untitled (Boltz, Eckardt, Mueller & Graef, …), 2009, paper / beeswax, 102 x 73 x 6 cm

Untitled (Rosa Klett, Kueferwerkzeug, Zimmer hinten rechts), 2009, paper / beeswax, 102 x 73 x 5 cm

Detail Untitled (Rosa Klett, Kueferwerkzeug, Zimmer hinten rechts), 2009, paper / beeswax, 102 x 73 x 5 cm

Sketchbook, 2009, pencil on paper, 9 x 14 cm

Depot | Herbert Stattler, Kunst im Dialog mit dem Stadtmuseum [art in dialog with the city museum]

The catalogue is published on the occasion of the solo exhibition of the same name at the Stadtmuseum Tübingen 2009.

Editors Evamarie Blattner und Karlheinz Wiegmann

Text Christine Heidemann

Graphic design Christiane Hemmerich Konzeption und Gestaltung

Photography Peter Neumann

21.0 x 27.3 cm, 16 drawings, saddle-stitching, softcover with 2 flaps, 14 pp. each with flap, English and German.

Tübingen 2009

ISBN 978-3-910090-97-2

Kornhausstrasse 10

D-72070 Tübingen

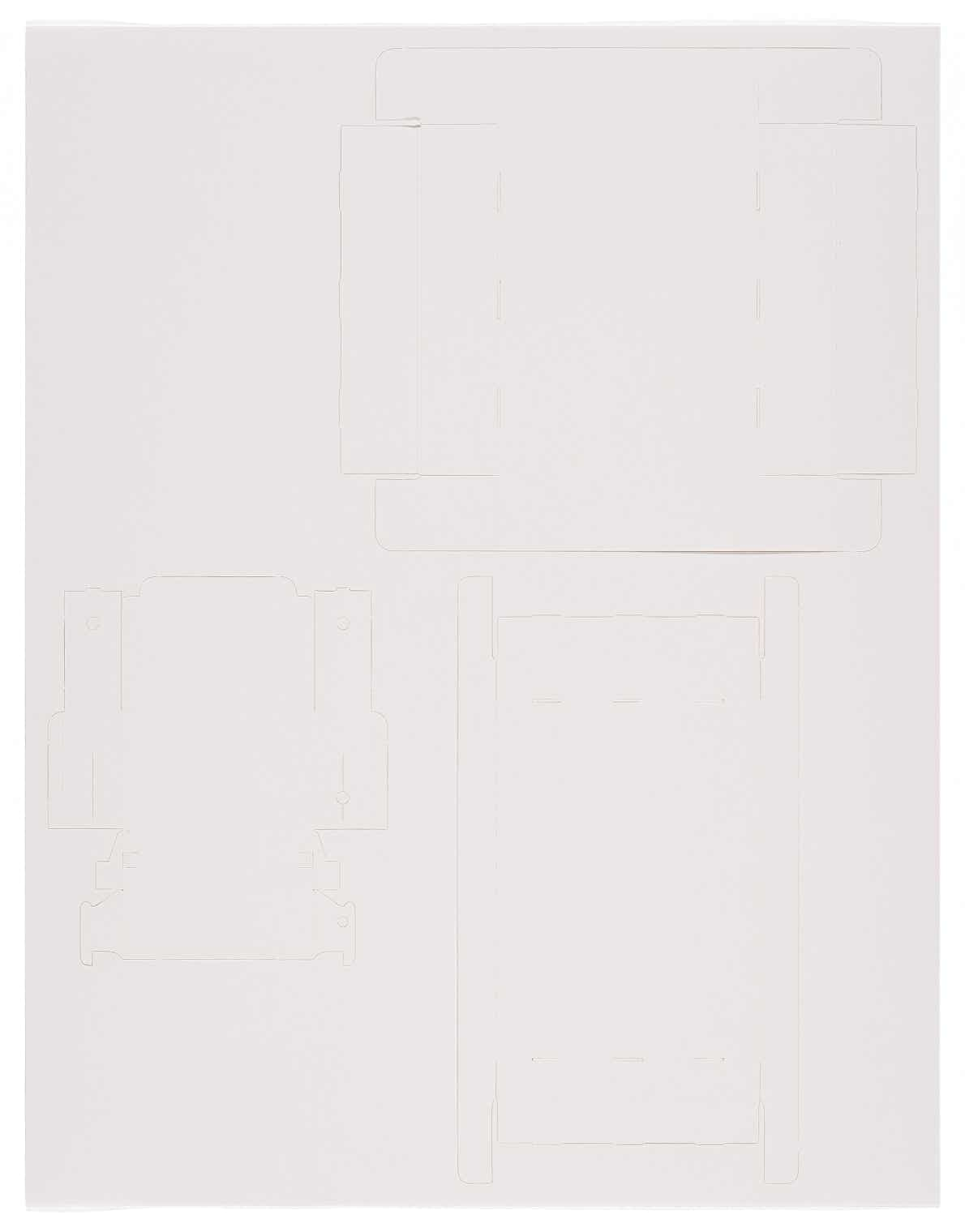

Special Edition

›Depot | Herbert Stattler, Kunst im Dialog mit dem Stadtmuseum‹ is also available as numbered and signed special edition (1/55 – 55/55 + 3 AP) featuring one card modeling for the two scaled archive boxes of the Stadtmuseum Tübingen in a bag of glassine paper. Format of the card modeling: 19 x 26 cm. Available at:

Galerie Druck & Buch

Berggasse 21/2

A-1090 Wien

An Archive of the Archives

Herbert Stattler’s artistic research in the depot of the Stadtmuseum Tübingen

Most of the time a museum conceals more than it reveals: In its archives with its shelves, cabinets and drawers the greater part of the inventory remains unknown to the visitor, to whom only a small range of objects is presented in the exhibition rooms. In the archives the »aesthetics of the concealed« is valid – many things remain invisible for a long time, sometimes not even the scientific staff has ever seen the entire collection. Most important for all archives is the particular system of order and cataloging, according to which the objects are inventoried. But sometimes in one and the same archive different principles of order coexist, for example if books are sorted differently from medieval handicraft, graphics, or animal taxidermy. However, in every depot, the containers and furniture in which the objects are archived are essential: folders, boxes, drawers, shelves and chests. Especially in the cabinet, says Gaston Bachelard in his »The Poetics of the Room« of 1957, a centre of order exists »that protects the whole house against boundless disorder. In this area, order rules, or rather order is a dominion.«1

Herbert Stattler has investigated this dominion of order artistically, questioning its structure and stability in a cryptic and pointed fashion. The starting point of his work in the depot of the Stadtmuseum Tübingen located in the former residence of Theodor Haering (1884-1964) is his curiosity and the wish to discover the concealed. In each of the three floors of the building Herbert Stattler has taken selected shelves and translated their structure into sketches, seven drawings, and three three-dimensional paper objects.

Ground Floor

Entering the house, the visitor encounters by chance the estate of Lotte Reiniger (1899-1981) who became famous in the 1920s for her silhouettes and animated silhouette films. One finds in numerous boxes, folders and cases stored on the shelves of the ground floor original silhouettes and further material from the estate of Lotte Reiniger, a big part of which has already been inventoried in the museum and when necessary restored. A permanent exhibition in honour of Lotte Reiniger was installed in 2008 in the exhibition rooms of the old granary in the centre of Tübingen.

Herbert Stattler chose one of the shelves in the Reiniger depot and noted sketches, measures, and keywords in small notebooks. These measurements served as a basis for a large drawing of the shelf similar to a geographic map, and more over, became the basis for a carefully executed paper object of the shelf on the scale of 1:5. Remarkably, only those details of the shelf that protrude are represented, thus ignoring the given limits of the furniture. These parts of the boxes and papers, however, are carried out with extreme precision. Each detail can be recognized, from folds in single boxes up to small slips of paper sticking out in some places. Herbert Stattler’s drawings, as well as the paper works, are snapshots of a situation in the depot where mainly the Reiniger collection is still in a constant movement, being continuously dealt with by the archivists. The subject of Herbert Stattler’s time-consuming artistic work is a situation that in the next moment might look totally different. He chooses this subject with the utmost care and this care corresponds with the care that is necessary day by day for the administration of a collection.

The exhibition in the Theodor-Haering-Haus presents the sketches, drawings, and paper objects side by side with the corresponding shelves. This direct proximity works as a reference that research work in an archive can never reach a state of stability. Due to regrouping of objects, exhibitions and recently acquired objects, it is subject to a constant change.

Even though Herbert Stattler’s paper works are extremely precise, it is not a matter of an absolutely true copy of the shelf but rather a translation of given structures into a model. A model always is a representation, a copy of something. On the one hand, a model tries to represent an object as truly as possible. On the other hand, at the same time it leaves out aspects of the underlying original, or for that matter the basic theory in favour of the abstraction. The paper model oscillates between realistic representation and abstraction and exactly the so created »areas in between« transfer the model into a formally extremely ambitious and appealing artistic work. Furthermore, the reduced yellowish-pink shimmering white of the paper treated with beeswax strongly contrasts with the colourful original and thus once again contributes to the abstraction of the model. The things themselves are emphasized and at the same time become inferior to the surface. The objects in the boxes and cases remain invisible – in this way the paper model also conceals more than it reveals in the end. This, however, makes its quality as a singular artistic work even more evident.

First Floor

Leaving the ground floor behind and reaching the first floor of the building, the visitor comes across about 500 years of the city history of Tübingen, conserved mainly in numerous three-dimensional objects of different types. And moreover, it is documented in the extensive collection of graphics, paintings and maps. In the room for the paintings the different sizes of the objects make it difficult to store them on the shelves: Some of the frames are too big for the shelves and protrude similarly to the boxes in the Reiniger archives. Rolled-up sheets of paper lie in the upper shelves, some of them also sticking out. Herbert Stattler’s translation of one of the shelves in the first floor into drawings and paper object again represents the overhanging parts. Here, too, the details are rebuilt precisely: The folded edges of the big cardboards separating the single paintings from each other or the creased papers of the rolls lying in the upper shelves can be recognized clearly. At the same time, there are many straight and empty areas in those parts where nothing sticks out of the shelves. In this way, here again an interaction between realistic copy and abstraction develops, which makes up the special charm of the paper works.

Attic

The last station of the artistic research in the archives of the Stadtmuseum Tübingen is the attic of the building. Finally, the paper works in all of the three floors of the depot offer a kind of cross section of the entire collection. In this area, mainly those objects are stored which are still in the state before the actual archiving or which are too big and bulky for being adapted to the systematic manner in the ground floor and the first floor. Recently acquired objects or donations of a complete estate always put the existing systems of order in a museum to the test: Can everything be integrated into the system, can it be catalogued properly? Is there room enough in drawers, cabinets and shelves? Most objects in the attic still await this interrogation – in this area of the archives it once again becomes obvious how narrow the line between the »dominion of order« and »boundless disorder« can be.

For the transformation into Herbert Stattler’s own archive of the archives this part of the collection offers a special attraction, for here it is not so much a sequence of similar parts rather than a coexistence of totally different objects and forms. There is a protruding door with a part of the lock dangling in the air, piled up wicker baskets are recognizable, as well as a lot of walking-sticks and other oblong objects, for example a roll of wallpaper and an umbrella stuffed, apparently unsorted, into a further basket.

The Museum as Ideological Room

The translations of the shelves in the attic into drawings and paper models make it again especially clear of what consists Herbert Stattler’s main interest in the inventory of the museum when performing his artistic work: Exactly these moments within a collection where the deficiencies and coincidences become visible, which – besides its systems of order – also define the structure of the archives. This might be something that is too big to fit into the furniture of the archives; objects that differ so much in form and size that they disturb the planned order of a single shelf or just the yet unorganized things that await integration into the archives. These obstinate objects are the very focus of Herbert Stattler’s attention – they produce structures which raise his interest formally, too.

The background of Herbert Stattler’s work is occupied by the question how a collection of a museum develops at all and who determines on which basis what things are placed in the museum and what is rejected. This power of definition of the museum, which depends to a high degree on time and ideology, has always been the subject of many artists (besides theorists such as Walter Benjamin, Michel Foucault or Paula Findlen), for example Hans Haacke, Mark Dion and above all Marcel Broodthaers who has devoted himself to the deconstruction of the institution »museum« and its presentations and representations since the late 1960s.2 His »Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles, XIXeme Siècle« (1968-72) which he installed in his apartment in 1968 for the first time was an ironically twisted display of the presentation techniques of a museum. It put into question impressively the symbolic representation of power by concentrating on the motif of the eagle in different variations. The »eagle-museum« consisted of postcards, cheap and more valuable objects with the eagle-motif, small sculptures, signs and posters drawn and lettered by Broodthaers as well as numerous cases in which the objects had been stored before. In the four years of its existence Broodthaers’ museum had no permanent place and no permanent collection. It always changed depending on where it was shown and which objects were added to or removed from the collection. Broodthaers exhibited primarily those elements that define the »aesthetic production and reception [of the museum] that, however, usually remain unconscious and invisible.«3 He performed this by grouping the objects into ensembles in which origin, material, and the age of things seemed to play no role, based rather on formal aesthetic criteria; furthermore, by labelling the exhibits. In a way he turned inside out and transformed the place »behind the scenes« of the exhibition rooms into the real place of his own museum. The art critic Craig Owen says: »Broodthaers’ preoccupation with the shell, and not the kernel – the container and not the contained – not only overturns a longstanding philosophical prejudice that meaning and value are intrinsic properties of objects; it also stands as an acknowledgement of the role of the container in determining the shape of what it contains.«4 Brodthaers discussed the museum’s power of definition, systematizations and classifications, expertise and hobby, the real value of the goods and the beauty of the banal, as well as the symbolic value of the objects elevated to the status of museum’s objects, the subject position of the collector and the curator, the arbitrariness of language and the logistics of the depot and the exhibition.5

Also the constellation of the inventory in the Stadtmuseum Tübingen is defined, as in every other museum, by numerous factors such as these. Some of the supplements added to Herbert Stattler’s actually untitled works give hints concerning the origin of the objects in the corresponding shelves by quoting the names of the former owners as in the case of a drawing and a paper object that are labelled: (Boltz, Eckardt, Müller & Gräf, …). Mainly in the case of donations first of all the objects are sorted and inventoried in the archives and finally exhibited, possibly.

Finally, the role of Theodor Haering is not at all insignificant for the perception of the city museum’s depot. After his death in 1964 Haering willed his former residence to the city of Tübingen, although this is of no consequence to the inventory itself. Due to his open commitment to the National Socialists’ politics, Theodor Haering, who was a professor of philosophy at the University of Tübingen, was and still is a controversial figure. Haering was awarded the title »honorary citizen of Tübingen« and the building in which since 1967 the depot of the Stadtmuseum is located, was named »Theodor-Haering-Haus.« These matters have been discussed by Tübingen politicians again and again. They will likely remain a controversial topic in the near future.6

Archiving the Archives

Besides the reflexion of all these factors which define a museum respectively, a collection, and its perception, it is also and above all the process of working with the objects that is the focus of Herbert Stattler’s interest. He is driven by a fascination with the scientific order of things and the methods of its adoption in which in the end it is not so much a question of the objects per se but their handling in the archives. His own meticulous report of different snapshots from the depot of the Stadtmuseum Tübingen and the translation of his measurements into the three-dimensional paper works in a way is also the adaptation of the tedious work of the archivist for whom accuracy and traceability are most critical. It is true that Herbert Stattler records the selected situations in the archives up to the smallest detail and with an immense expenditure of time (although they are only snapshots) but it is not without a sense of humour. In a very pointed way he implicitly raises the question of the relation between the meaning of the objects in the archives and the time and effort that are necessary to inventory and archive them.

The result of his artistic research work is an archive of the archives en miniature in which every drawing and sketch and every single paper object, like distillates, represents the characteristics of this depot from a very personal point of view.

Christine Heidemann

Translated by Heidrun Frey

![Detail of »Untitled (Lotte Reiniger)«, 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm Pencil drawing of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/n/depot-detail-01_small-1176.jpg)

![Detail of »Untitled (Lotte Reiniger)«, 2009, paper / beeswax, 102 x 73 x 6 cm Paper object of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/v/depot-detail-09_small-1176.jpg)

![»Untitled (Lotte Reiniger)«, 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm Pencil drawing of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/0/depot-01-2392.jpg)

![Detail of »Untitled (Lotte Reiniger)«, 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm Pencil drawing of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/p/depot-detail-01-2400.jpg)

![»Untitled (Boltz, Eckardt, Mueller & Graef, …)«, 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x73 cm Pencil drawing of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/a/depot-02-2396.jpg)

![Detail of »Untitled (Boltz, Eckardt, Mueller & Graef, …)«, 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x73 cm Pencil drawing of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/a/depot-detail-02-2400.jpg)

![»Untitled (Bassenge, Dostmann, Mayer, …)«, 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm Pencil drawing of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/0/depot-03-2396.jpg)

![Detail of »Untitled (Bassenge, Dostmann, Mayer, …)«, 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm Pencil drawing of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/n/depot-detail-03-2400.jpg)

![»Untitled (Depperich, Schwabinger, Vogt, …)«, 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm Pencil drawing of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/e/depot-04-2394.jpg)

![Detail of »Untitled (Depperich, Schwabinger, Vogt, …)«, 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm Pencil drawing of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/8/depot-detail-04-2400.jpg)

![»Untitled (Rosa Klett, Kueferwerkzeug, Zimmer hinten rechts)«, 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm Pencil drawing of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/r/depot-05-2392.jpg)

![Detail of »Untitled (Rosa Klett, Kueferwerkzeug, Zimmer hinten rechts)«, 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm Pencil drawing of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/e/depot-detail-05-2400.jpg)

![»Untitled (Buehler, Honold, Zimmer, …)«, 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm Pencil drawing of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/0/depot-06-2398.jpg)

![Detail of »Untitled (Buehler, Honold, Zimmer, …)«, 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm Pencil drawing of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/l/depot-detail-06-2400.jpg)

![»Untitled (2 Archivschachteln)«, 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm Pencil drawing of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/h/depot-07-2390.jpg)

![Detail of »Untitled (2 Archivschachteln)«, 2009, pencil on paper, 102 x 73 cm Pencil drawing of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/6/depot-detail-07-2400.jpg)

![»Untitled (Lotte Reiniger)«, 2009, paper / beeswax, 102 x 73 x 6 cm Paper object of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/e/depot-08-2400.jpg)

![Detail of »Untitled (Lotte Reiniger)«, 2009, paper / beeswax, 102 x 73 x 6 cm Paper object of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/a/depot-detail-08-2400.jpg)

![»Untitled (Boltz, Eckardt, Mueller & Graef, …)«, 2009, paper / beeswax, 102 x 73 x 6 cm Paper object of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/8/depot-09-2400.jpg)

![Detail of »Untitled (Boltz, Eckardt, Mueller & Graef, …)«, 2009, paper / beeswax, 102 x 73 x 6 cm Paper object of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/n/depot-detail-09-2400.jpg)

![»Untitled (Rosa Klett, Kueferwerkzeug, Zimmer hinten rechts)«, 2009, paper / beeswax, 102 x 73 x 5 cm Paper object of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/h/depot-10-2400.jpg)

![Detail of »Untitled (Rosa Klett, Kueferwerkzeug, Zimmer hinten rechts)«, 2009, paper / beeswax, 102 x 73 x 5 cm Paper object of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/c/depot-detail-10-2400-1.jpg)

![Sketchbook, 2009, pencil on paper, 9 x 14 cm Pageview of the sketchbook of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/a/depot_sketchbook-02-1100.jpg)

![Sketchbook, 2009, pencil on paper, 9 x 14 cm Pageview of the sketchbook of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/0/depot_sketchbook-04-1100.jpg)

![Sketchbook, 2009, pencil on paper, 9 x 14 cm Pageview of the sketchbook of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/l/depot_sketchbook-06-1100.jpg)

![Sketchbook, 2009, pencil on paper, 9 x 14 cm Pageview of the sketchbook of the series »Depot« [Storage] by Herbert Stattler.](../images/t/depot_sketchbook-08-1100.jpg)